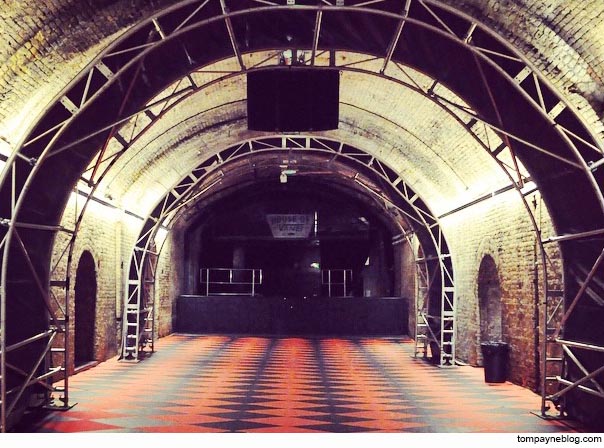

The Old Vic Tunnels underneath Waterloo Railway Station was - just a few years ago - nothing more than a few damp and derelict railway arches. In 2009 the space opened its doors as an arts and performance space and hosted dozens of amazing musicians, including the amazing Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros and saw the UK premiere of Banksy's Exit Through the Gift Shop.

After more than a year in disuse once again, the space reopened just a few weeks ago as House of Vans. Luckily enough, I was able to check out the new venue a few days after it opened. It's pretty amazing.

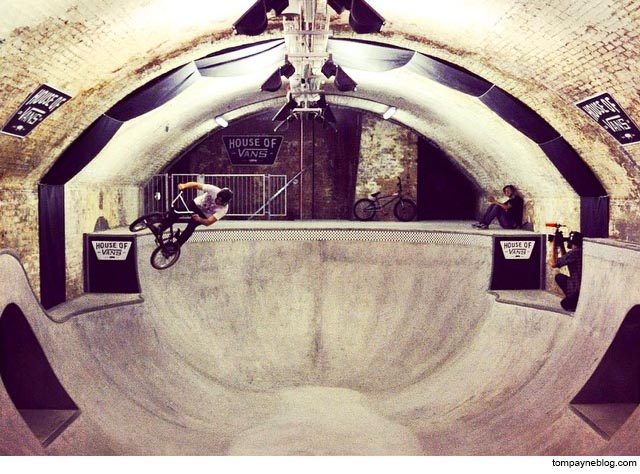

Nestled away in the Leake Street corner of the Station, the space comes complete with a street course, bowl section, a couple of bars, art space and music venue.

Once again, London has proved that innovative and creative thought to architecture and design can over come even the tightest physical limitations. When compared to the Vans parks spread across the United States, the London setup looks a little small. But through incredible layout technique, the creators of this venue have somehow managed to create what is a probably a far more interesting and active space than any large warehouse could offer. The coolest part is that it sits just a few metres underneath a a major railway line in the midst of one of the most amazing city centres in the world.

Perfect for an afternoon skate, Friday night party...or both. Check it out.

Feature image courtesy Domus. Images above by Tom Oliver Payne.