I hadn’t been to Amsterdam for a few years, so I was pretty excited to head back there last week.

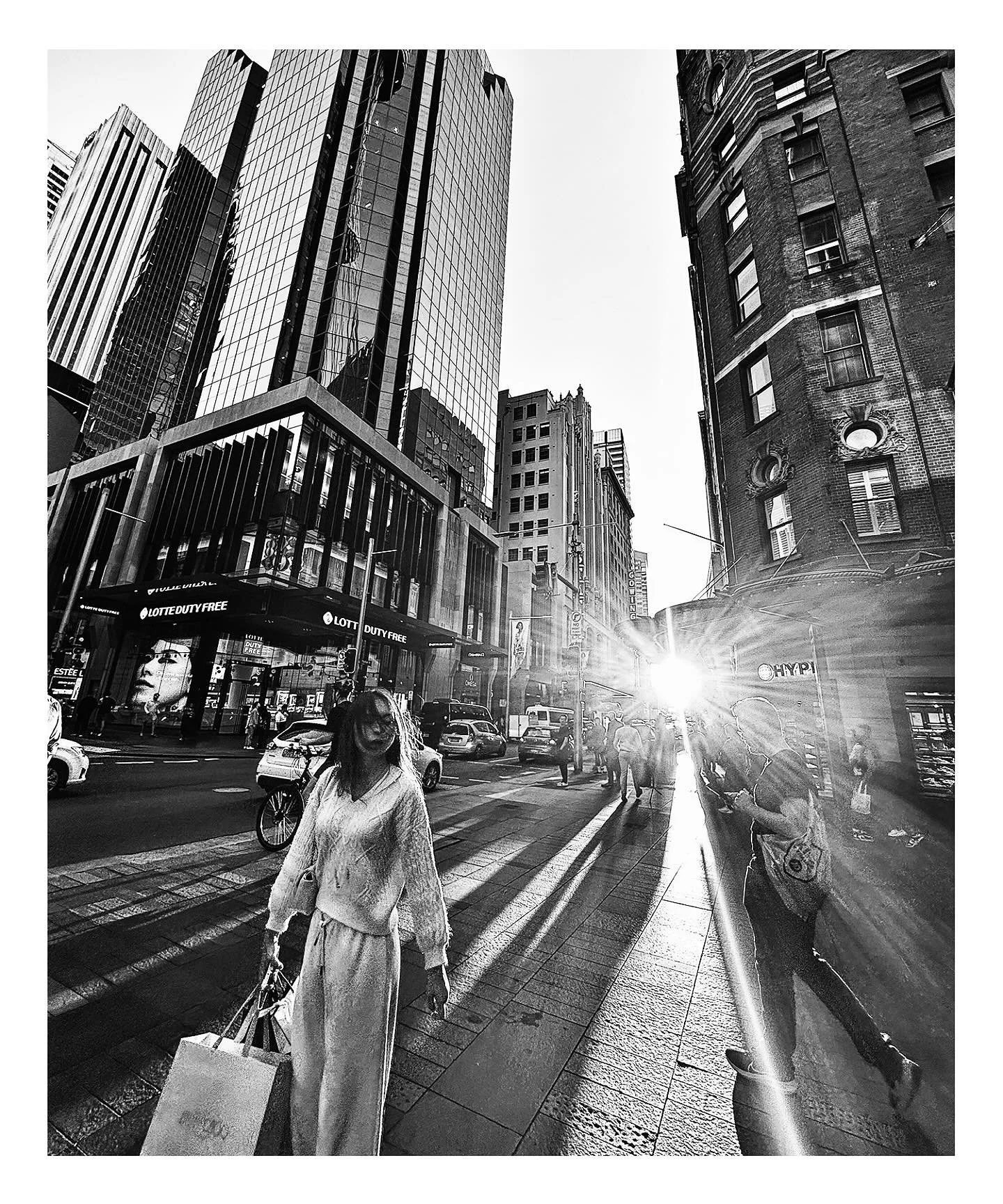

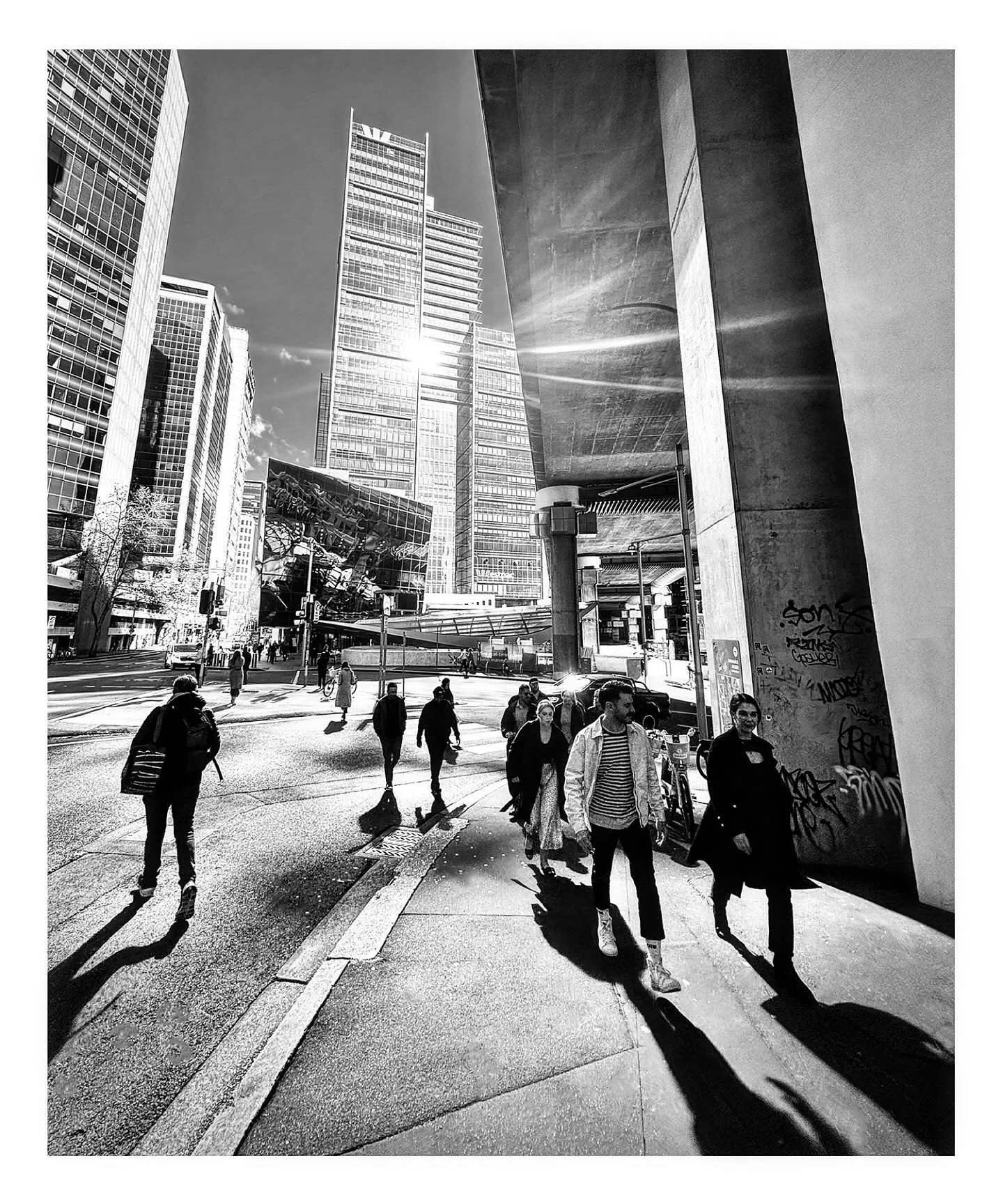

You can learn a lot about a place just by observing it. Café culture, nightlife and architecture are all indications of what a city is like. Even subtler than that is what people wear, how they travel and converse. People-watching – in my opinion - is a far better way to understand a city than reading a book or heading out on a bus tour. After a few days of cruising around the city by foot and bike, I made a couple of observations below.

1. bikes are still loved in winter

Amsterdam is a bicycle city – just about everyone knows that. Coming from the hot and sweaty landmass on the other side on the other side of the world, I’ve always wondered how Amsterdam’s cold winter temperatures and minimal daylight hours impact upon people’s desire to ride. In short, this seems to have very little effect.

Early morning before the sun is up and the air is ice cold, bike paths into the city centre are packed with bikes. While the weather may sound a little grim, people aren't deterred at all. Actually, it would be interesting to understand the happiness levels of car drivers, public transport users and bikes riders in winter in Amsterdam. I’m certain those on bikes would be far happier than the rest. As in any city, people on bikes can have random conversations, stop in and out of shops en-route and observe early morning street life. Driving a car simply doesn't give you the joy that riding a bike does.

Over and over I've been told that cities should not – or can not – adopt Dutch cycling culture because of weather and climate. Unless you're talking these temperatures, that's a load of rubbish. I’ve heard this argument in cities with far milder temperatures than Amsterdam, and with far less rain too. When you have the right infrastructure and a culture supportive of bikes, cycling works in all times of the year.

2. Too much of one type of tourism is damaging the city centre

I know this is a pretty bold statement and is based on observation only. But the city centre is absolutely packed to the brim with 'Euro-trip' Australians, English hen parties and stoned Americans. Not that I have a problem with any of this in principle, but when a beautiful historic city centre is inundated with drug and party tourism culture, it begins to look and feel a little naf. Rather than a liberal city that is accepting of liberal attitudes, a large part of its economy looks to be solely reliant on a single type of tourism. As a result it feels like the city is developing around its tourism narrative rather than evolving as an actual place. This isn't good for locals or the future of the tourism industry.

The liberal Dutch attitude is a wonderful thing. The problem however, is that other countries are not so liberal. As a result, Amsterdam city centre has become a mecca for 'lads on tour’. Tacky neon signs hanging from beautiful brick work, café signs reading “American steaks” and an abundance of English football jerseys are just a few telling signs that the city centre is in stress.

Now, I know that the internationalisation of urban centres is well-discussed problem in the age of globalised economies and broken-down borders, but I’d argue that city’s like Amsterdam need to understand how its tourism economy can be essentially self-destructing. It's becoming increasingly obvious that the commercialisation of places and products actually leads retail centres to become far less competitive in a world where distinctiveness is increasingly vital to attract and maintain a healthy tourism trade. As place branding and marketing has grown in importance, urban markets in London for example, are quickly trying to rediscover what made them unique in the first place.

Perhaps its time for Amsterdam to recognise and enhance what makes the city a great place for locals. This will naturally translate into a strength for tourism.

3. People are amazing

The best part about going to a new city is meeting new people, and generally when you step put into a new place you get a vibe straight away. Are people smiley, polite, and do they have a warm aura? Although I'd been to Amsterdam before, I was immediately overwhelmed with how amazing people were. There is so much warmth and love in that city - it's incredible.... Maybe it's just a Dutch thing!

How well do you know Amsterdam? Any thoughts on these observations?

Photos by Tom Oliver Payne.